Sleep problems affect 50-80% of children with autism, far exceeding the 25% prevalence in typically developing children, and often persist from infancy into adolescence. These disturbances, including prolonged sleep onset and frequent night wakings, exacerbate core autism traits, behavioural challenges, and family stress, underscoring the need for targeted assessment and intervention.

Biological Underpinnings

Sleep problems in autistic children aren’t just about bedtime battles—there are real biological differences happening in the brain and body. Research shows that autistic children often have imbalances in certain brain chemicals (like serotonin and melatonin) that affect their natural sleep-wake cycles. Some children have genetic variations that mean their bodies produce less melatonin at night, which is why they struggle to feel sleepy at bedtime. Studies have even found that certain brain differences present from infancy can predict which children will develop sleep difficulties later on.

When researchers study autistic children’s sleep in detail using special monitoring equipment, they find significant differences compared to non-autistic children. Autistic children spend less time in REM sleep—the deep dreaming stage that’s crucial for memory and learning (about 15% of the night compared to 23% in other children). They also wake up more frequently during the night. These disruptions mean the brain doesn’t get the restoration it needs, which affects memory, learning, and how children cope during the day.

Types of Sleep Disturbances

The most common sleep challenges include children refusing to go to bed or taking more than 20 minutes to fall asleep (affecting about half of autistic children), waking up during the night, not getting enough sleep overall, and waking too early in the morning.

Many autistic children (around 53%) experience things like night terrors or sleepwalking. About a quarter have breathing difficulties during sleep, such as snoring or sleep apnea. Nearly a third struggle with excessive tiredness during the day, even when they seem to have slept enough.

These patterns change as children grow. Younger children are more likely to resist bedtime and experience night terrors or sleepwalking, while teenagers tend to struggle more with falling asleep at night and feeling exhausted during the day.

Assessment and Contributing Medical Factors

Start by getting a clear picture of your child’s sleep patterns. You can use questionnaires designed specifically for tracking children’s sleep problems, or keep a sleep diary to record what’s actually happening night by night. There are free apps available like SNappD that can help you track this objectively.

It’s important to rule out physical problems that might be disrupting sleep. Common culprits include:

- Tummy troubles: Constipation (which affects about a quarter of autistic children), reflux, or other pain that makes lying down uncomfortable

- Dental issues: Teeth grinding or untreated tooth decay, especially if your child finds tooth-brushing difficult due to sensory sensitivities

- Other medical conditions: Allergies, low iron levels, low vitamin D levels, epilepsy, or side effects from medications

If you suspect your child has breathing problems during sleep (like snoring heavily or seeming to stop breathing briefly), ask your doctor about a sleep study. It’s also worth considering whether anxiety or ADHD might be contributing to sleep difficulties—these often go hand-in-hand with autism and addressing them can significantly improve sleep.

Management Strategies

For sleep problems in autism, it is vital to focus on behavioural interventions as the first line of treatment, and to take your time with these – several weeks of persistent effort is the minimum to to give any new strategy a fair try. Medication with melatonin can be effective (please see below) but even medication only works well if used hand-in-hand with a behavioural approach.

Research has shown that among the various behavioural interventions available, exercise stands out as the most effective option for improving sleep quality and duration for children on the autism spectrum.

Structured physical activities such as swimming, cycling, and trampolining work particularly well for children with autism, as these exercises provide sensory input whilst being predictable and repetitive.

When addressing demand avoidance around exercise, it’s essential to incorporate your child’s special interests, such as using weighted balls themed around dinosaurs or creating obstacle courses with their favourite characters. Building exercise into daily routines rather than presenting it as a separate task, offering choices between different activities, and starting with very brief sessions can help reduce anxiety around new activities, whilst gradually establishing positive associations with physical movement.

Routines and Sleep Hygiene

The goal is to help your child learn to fall asleep on their own, so they’re not depending on you being there every night. This happens gradually—you slowly reduce how much you’re involved in bedtime while making your child feel safe and capable throughout the process.

This might look like moving your chair a little further from the bed each night, staying for slightly less time, or checking in at longer intervals. At the same time, you praise and reward each small step of independence—whether that’s verbal encouragement, a sticker chart, or the promise of a special activity the next morning. The key is making changes slowly and predictably, so your child builds confidence rather than feeling abandoned.

Over time, your child starts to associate bedtime with their own ability to settle down, rather than needing you right there. They develop skills to soothe themselves and feel safe falling asleep independently. It takes patience and consistency, but these gradual changes help shift the balance from you doing the work of getting them to sleep, to them being able to manage it themselves.

Sensory and Lifestyle Modifications

Pay attention to your child’s sensory needs. Some children sleep better with a weighted blanket providing gentle pressure, white noise blocking out distracting sounds, or other calming sensory input that helps them feel settled and secure.

Make sure your child gets plenty of physical activity during the day—things like climbing, pushing, pulling, or jumping that give their body that “heavy work” input. Just avoid vigorous exercise too close to bedtime, as this can be too alerting. Also look at diet: cut out caffeine (which hides in chocolate, fizzy drinks, and some sweets), and work with your doctor to address any tummy problems like constipation or reflux that might be disrupting sleep.

Pharmacological Options

Melatonin is the most common sleep medication for autistic children. A dose of 1-6mg taken before bedtime can help children fall asleep faster, and it works for about 60-80% of children—especially when combined with good sleep routines and bedroom setup. Keep tracking sleep patterns in a diary so you can see whether it’s actually helping. Working with a team of professionals (like your GP, paediatrician, and sleep specialists) tends to give the best results.

Short-term use of melatonin (up to 3 months) is generally considered safe. However, we don’t yet have strong research on the long-term safety of melatonin in children, so if your child needs it for longer periods, they should be monitored regularly by a healthcare professional to check for any side effects or concerns.

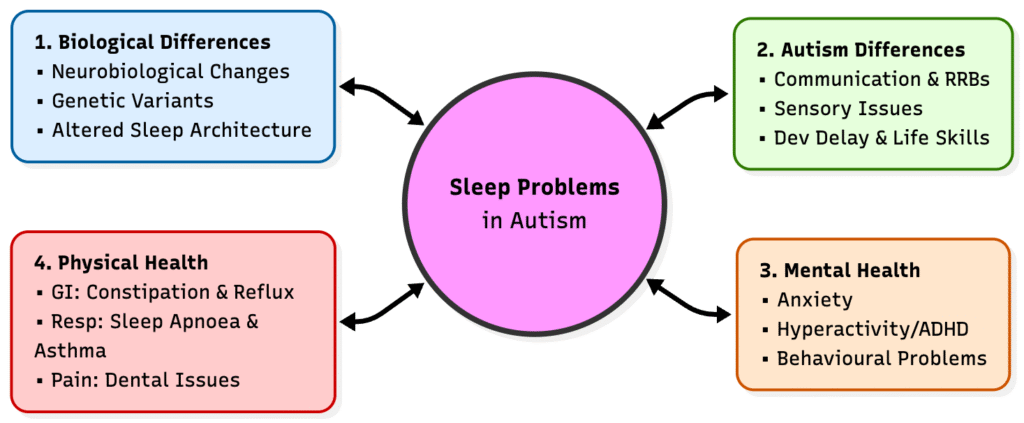

This diagram shows how sleep problems in autism rarely have a single cause: biological differences in brain development, core autism features (communication, repetitive behaviours, sensory issues, daily living skills), mental health difficulties (anxiety, associated hyperactiity or comorbid ADHD, behaviour), and physical health problems (constipation, reflux, breathing issues, pain) all interact and feed into each other. By making small, steady adjustments in each of these areas – for example, treating pain and constipation, supporting communication and sensory needs, and addressing anxiety – families and clinicians can gradually “nudge” the whole system towards better, more settled sleep over time.

Final Thoughts: The Power of Movement

While the path to better sleep involves addressing many interconnected factors, from biology to bedtime routines, regular physical activity stands out as a powerful, natural tool in your arsenal. Research consistently highlights exercise not just for physical health, but as a potent regulator for the autistic brain, helping to burn off excess energy, reduce anxiety, and reset the body’s internal clock. Whether it’s a structured swimming session, a bounce on the trampoline, or a walk in the fresh air, integrating movement into the day provides the sensory “heavy work” that many autistic children crave to feel grounded. By making exercise a predictable, enjoyable part of daily life—tailored to your child’s unique interests, you aren’t just building stronger bodies; you are laying the physiological foundation for calmer evenings and deeper, more restorative rest.

Resources

• Cerebra Sleep Advice Service Excellent one-to-one support for families of children with brain conditions (including autism). They offer a detailed “Sleep Guide,” a sleep card system for specific issues, and a telephone advice service where you can speak directly to a sleep practitioner if you meet their criteria and submit a sleep diary.

• The National Autistic Society (NAS)

Their website has a comprehensive “Sleep – a guide for parents” section covering strategies like visual timetables, sensory audits of the bedroom, and melatonin info. They also have an Autism Services Directory to find local support groups.

• Sleep Action (formerly Sleep Scotland)

While originally focused on Scotland, they provide training and resources UK-wide. They run a sleep support line and have specific expertise in neurodevelopmental sleep issues.

References

Yang H, Lu F, Zhao X, et al. Factors influencing the effect of melatonin on sleep quality in children with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 2025;29(4):262. doi:10.1007/s11325-025-03432-x

Händel, M., Andersen, H., Ussing, A., Virring, A., Jennum, P., Debes, N., Laursen, T., Baandrup, L., Gade, C., Dettmann, J., Holm, J., Krogh, C., Birkefoss, K., Tarp, S., Bliddal, M., & Edemann-Callesen, H. (2023). The short-term and long-term adverse effects of melatonin treatment in children and adolescents: a systematic review and GRADE assessment. eClinicalMedicine, 61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102083.

Zisapel, N. (2022). Assessing the potential for drug interactions and long term safety of melatonin for the treatment of insomnia in children with autism spectrum disorder. Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology, 15, 175 – 185. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512433.2022.2053520.